A common approach for NBA teams is to surround their superstars and offensive playmakers with efficient shooters who are more than willing to hit the open three-pointer when given a chance. The playmakers draw much of the defense’s attention and command double and triple teams. Therefore, it is prudent to collect efficient shooters around them.

Do the numbers support this way of thinking? Do teammates of superstars take more threes when the superstar is on the floor? To answer these questions, I turned to the play-by-play data available at Basketball Geek. I picked 10 superstars and broke down their team’s three-point shooting data to see how often the team shoots three-pointers when the player is on the court versus how many it shoots when the player is off the court. The superstar’s own three-point shooting was not counted. To measure three-point frequency, I calculated the total number of three-point attempts divided by the total number of field goal attempts.

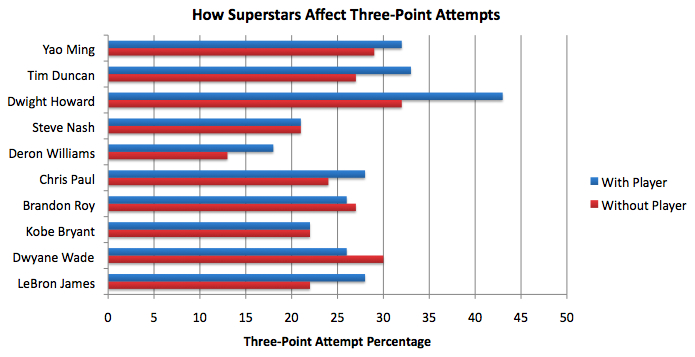

Let’s take a look at the chart:

As you can see, most of the players increase the three-point frequency of their teammates while they are on the court. The most extreme case is Dwight Howard, who increases the Magic’s three-point attempt percentage from 32% when he’s off the court to a staggering 43% when he’s on the court. In other words, if you’re playing with Dwight Howard, there’s a 43% chance your next shot will be a three-pointer. Big men in general tended to have the largest effects on three-point frequency, supporting the common strategy of having a dominant post player who demands double teams and can kick out the ball for open threes. The Magic, in particular, killed teams with this strategy.

Two of the three point guards I looked at had similar effects as the big men, while swingmen were a mixed bag.

Why do some superstars not increase the three-point frequency of their teammates? I had a hypothesis about this: when those particular players subbed out of the game, three-point shooters were replacing them. This, of course, would make the three-point frequency when those superstars were off the court deceptively high.

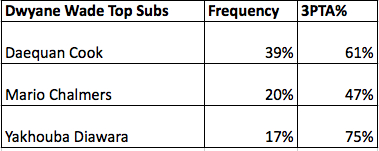

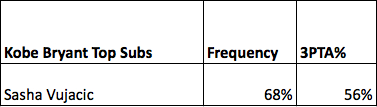

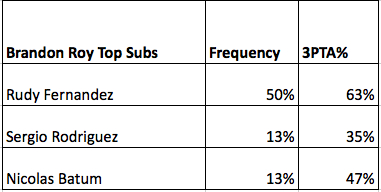

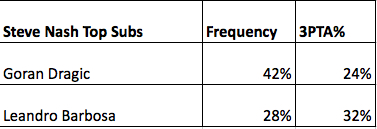

To test my hypothesis, I went through the play-by-play data of the four superstars that did not increase three-point frequency: Dwyane Wade, Kobe Bryant, Brandon Roy, and Steve Nash. Which players were substituting in for them? The following tables report the top subs for each player and the three-point attempt percentages for those subs:

Except for Steve Nash, it appears as though my hypothesis was correct. Dwyane Wade and Kobe Bryant, in particular, had subs that can be considered three-point specialists. If these superstars had subs that were equally as fond of two-pointers, I imagine their impact on team three-point frequency would be similar to the other superstars I looked at.

So what’s the deal with Nash? His subs weren’t particularly in love with three-pointers, yet Nash did not increase team three-pointers. I think there could be two things behind this. For one, Nash is not a typical superstar that overwhelms his opponents with his physical abilities. He may draw the attention of defenders, but he’s certainly not demanding many double teams. Second, Nash may just be really good at setting up open looks by the basket, as I imagine Amare Stoudemire and Shawn Marion can attest. In the end, if one player doesn’t fit in with the rest of the superstars, I’m not very surprised if it’s Steve Nash.

It’s nice when the statistics confirm the common dogma among NBA teams. Teams collect three-point shooters to surround their superstars, and these strategies appear to be valid. These same shooters, when the superstar is off the court, don’t shoot nearly as many threes. I believe the results of this study should serve as further encouragement to NBA front offices that they should continue to acquire efficient, three-point shooting role players if they have a superstar on the roster.